An odd feature of java's secure random

The cli

To set the stage for this post I need to give some background; I work at a company which I will call Datadyne and we have a command line program which we usually call the cli. This program is one option with which our customers can interface with our platform and in particular it can be used to upload files, it’s not a particularly interesting tool but it has become essential in the pipelines of some of our customers. However, in some instances there have been reports of the cli simply freezing during upload. No crashing. No error messages. Nothing, but a hung terminal.

Openjdk

When I first started to care about the cli I had two jobs: 1. Swap out the underlying crypto engine and 2. Move some of our infrastructure from Oracle jdk to openjdk. The first task turned out to be easy enough with the java JCE provider framework which lets you code against a common api and swap out the provider on deployment. The second task was also easy as well but exposed a quirk; after running through a battery of tests the deployed openjdk code froze when deployed on infrastructure. It’s worth pointing out at that the crypto code was shared between the cli and the various infrastructure bits, but what’s changed here? Was openjdk able to generate code which could pass tests, but hit some failure case in production? Was there some strange interaction between the new crypto provider and openjdk? Were the cli and infrastructure freezes related? In a word; yes.

Openjdk on linux (but not all linux)

For the sake of brevity I’ll skip the investigation, but it turns out that on some distributions of linux openjdk defaults to /dev/random rather than /dev/urandom as a secure random source. As it turned out about half of our infrastructure was configured to use urandom and the others used random. For those new to the urandom v random discussion; urandom doesn’t block while random does. Making an edit to the java.security file in $JAVA_HOME/lib/security made for a quick fix, but it wasn’t the sort of fix we could deploy to customers. This is also partly why these changes got through testing; all the test machines were configured with urandom.

Old prejudices die hard

It would have been easy to blame the linux devs or over zealous cryptography researchers or the lizard people or whoever for making random block and chalk up the poor performance of our code to them. It’s easy to blame others and if you’ve spent any time in low entropy environments like Corporate America it’s certainly common, but it’s wrong. Do a quick search for slow /dev/random you’ll find a litany of complaints and the more you read the easier you’ll find it to be seduced by the implicit mantra that /dev/random is a poorly made device.

In truth /dev/random has been developed over many years by some of the best talent around and it is an exquisitely well made and highly performant device for what it is, however the design of /dev/random leads it to block in low entropy, high drain scenarios. This may change in the future, but today this is just a fact of life.

Use less entropy

So, how is this a unique problem? We’re running on fairly standard linux distros along side other java code which must have to deal with the same scarcity. Why is our code not working properly? Probably our code is a glutton of entropy and is putting far more demand on the system random than is reasonable. Doing a quick code search I came to some of our upload code which had one main loop

for (file : list){

datfile = encrypt_and_pack(file)

send(datfile)

}

The encrypt_and_pack function was making a new random key for each file, encrypting the file, adding some checksums and returning. This was disheartening to find as there’s nothing you can do here without compromising the security model. But surely there was something amiss. The true problem turned out to lie with the way in which we were generating random numbers. Deep down in the bowels of our codebase we had a few classes that looked like this

public final class EncryptingThingsHere {

...

public static byte[] getSomeBytes(int n) {

SecureRandom rng = new SecureRandom();

byte[] themBytes = new byte[n];

rng.nextBytes(themBytes);

return themBytes;

}

...

This looks innocuous enough, but what is the SecureRandom object? A SecureRandom is a thread safe, but fully independent random number generator to be used when you care about your numbers being unguessable. If you read the javadoc material alone you’d be forgiven in thinking that all SecureRandom objects share a JVM provided entropy pool. Certainly the docs never imply that there is any uniqueness to different instances. However if you inspect the source code for the SecureRandom implementation here you’ll find the following comment.

The returned SecureRandom object has not been seeded. To seed the

returned object, call the setSeed method.

If setSeed is not called, the first call to

nextBytes will force the SecureRandom object to seed itself.

This self-seeding will not occur if setSeed was

previously called.

That is, if a seed has not be explicitly set, then the first use of the object will call for seeding. Look back at the code above. We’re creating a new object and thus a new seed every time we call getSomeBytes. Horribly wasteful, but thankfully very easy to fix. In each of the offending functions we can create a single static SecureRandom object and just use that.

ex.

public final class EncryptingThingsHere {

final static SecureRandom rng = new SecureRandom();

public static byte[] getSomeBytes(int n) {

byte[] themBytes = new byte[n];

rng.nextBytes(themBytes);

return themBytes;

}

...

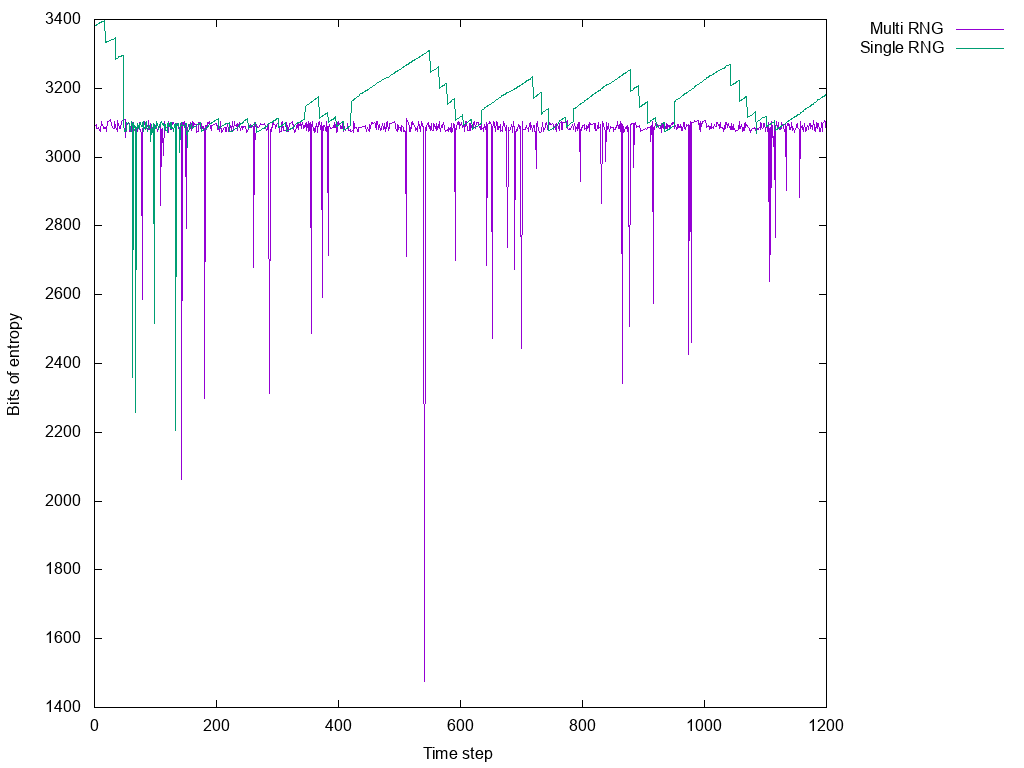

The results are pretty dramatic and are captured quite nicely in the following graph.

You can see the prior approach in purple and the new single RNG approach in green. The data for this graph came from checking /proc/sys/kernel/random/entropy_avail every 0.1s while the relevant code was running and then killed at two minutes. In the prior approach you see the available entropy when running the old code and it’s just dips with one precipitously large dip. Given a longer runtime or a system with less activity those dips could hit zero and simply halt the system. In green the new code which has the same dips early on, but is otherwise much more well behaved.

Wrap up

To close, I just want to draw attention back to those java docs. No where in there do they mention that the object constructor can be expensive. They discuss that the randomness source can block, but never that the act of creating a new SecureRandom will necessitate drawing on system entropy, nor what that can entail.

Thanks for reading

Example code (Added 2019-09-04)

After a related discussion with a colleague I made a simple example loop to show off the effects of the SecureRandom() constructor and figured I should post it here. This code spins in a loop and drains entropy from a linux system configured to use /dev/random.

import java.security.SecureRandom;

import java.nio.file.*;

import java.util.*;

import java.nio.charset.StandardCharsets;

public class entropy_test {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<String> lines = new ArrayList<>();

byte[] result = new byte[4];

short overflowCounter = 0;

while (true){

overflowCounter +=1;

result = new byte[4];

if (overflowCounter==0){

try {

Path file_path = Paths.get("/proc/sys/kernel/random/entropy_avail");

lines = Files.readAllLines(file_path, StandardCharsets.UTF_8);

} catch (Exception e) {}

for (String s : lines){

System.out.println(s);

}

}

SecureRandom sr = new SecureRandom();

sr.nextBytes(result);

}

}

}